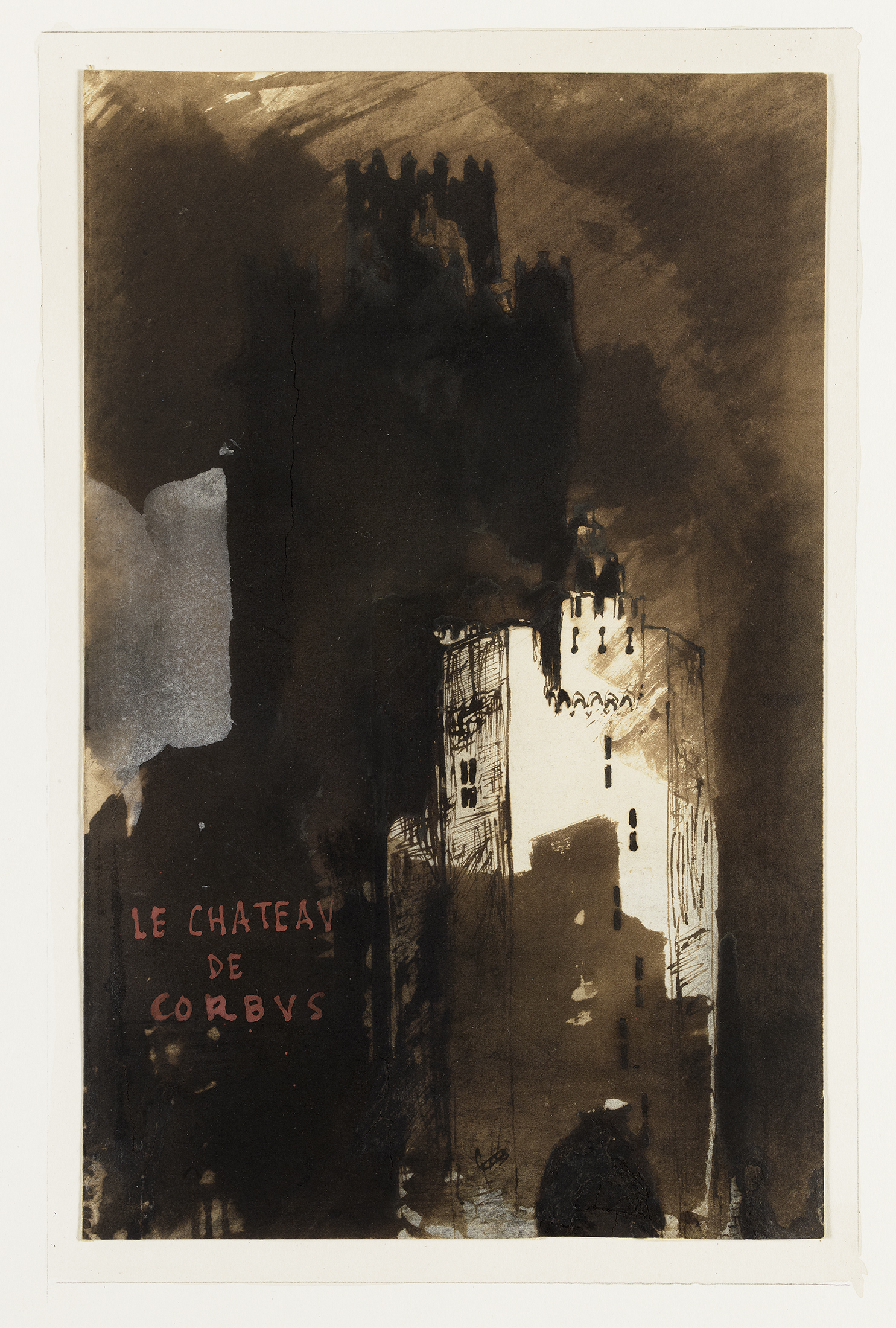

Victor Hugo was a prolific and talented draftsman who left some four thousand drawings, most of which are held by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Maison Victor Hugo in Paris. This graphic production was important to the writer: “I am very happy and proud of what you think of the things I call my pen drawings,” he wrote to Charles Baudelaire in 1860. Among his repertoire, landscapes hold a significant place, whether they be of sites Hugo visited during his travels, drawn in situ or from memory, or imaginary landscapes. Often inspired by a Middles Ages idealized through the lens of tragedy, these represent fortified cities, “fortresses,” and ruins, whose disturbing silhouettes are carved from spectral atmospheres. Le Château de Corbus is one of these; it is exceptional in that it finds its literary pendant in La Légende des siècles:

“The shepherd is affeared, and think the tower follows him;

Superstitions have made Corbus terrible;

It is said the Black Archer has taken aim at this fortress,

And that in its cellar The Great Sleeper still sleeps sound;

Because the villagers are easily afraid;

For legends grow and mix with phantoms of the mind

And in the smoke rising from the thatches,

The hearth gives birth to dreams, we see them ripple out

Fear in the fireplace’s drifting smoke.”“Eviradnus,” 1859

During his lifetime, Hugo sold no drawings, but sometimes gave them to friends, to his mistresses, and to other artists he admired. Le Château de Corbus was given to scholar and journalist Auguste Vacquerie (1819–1895), who was very close to the writer and his family: his brother married Léopoldine Hugo

The acquisition of this work by Beaux-Arts de Paris is essential to its drawing collection and its evolution. It is filled with a fine selection of Romantic drawings by Delacroix, Géricault, Chassériau, Isabey, and so on. With its castellated château emerging from the shadows through an “electric chiaroscuro” (Pierre Georgel), Le Château de Corbus perfectly complements the imagination of the painters of the era.

The self-taught Hugo drew with brush and ink but “ended up mixing crayon, charcoal, sepia, coal, soot and all kinds of strange mixtures that manage to render more or less what [he] saw, and above all, his spirit,” personifying an eminently independent manner. As early as 1863, Théophile Gautier noted the singularity of this approach, evoking “the transformation of a stain of ink or of coffee on an envelope, on the first paper to hand, a remarkably original landscape, a castle, a seascape where the collision of light and shadows produces an unexpected, startling, and mysterious effect.” This experimental and spiritual approach is echoed in the work of certain artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Le Château de Corbus, 1860 Brown wash and Indian ink, red and white gouache, 23 x 15 cm © Beaux-Arts de Paris, EBA 11198