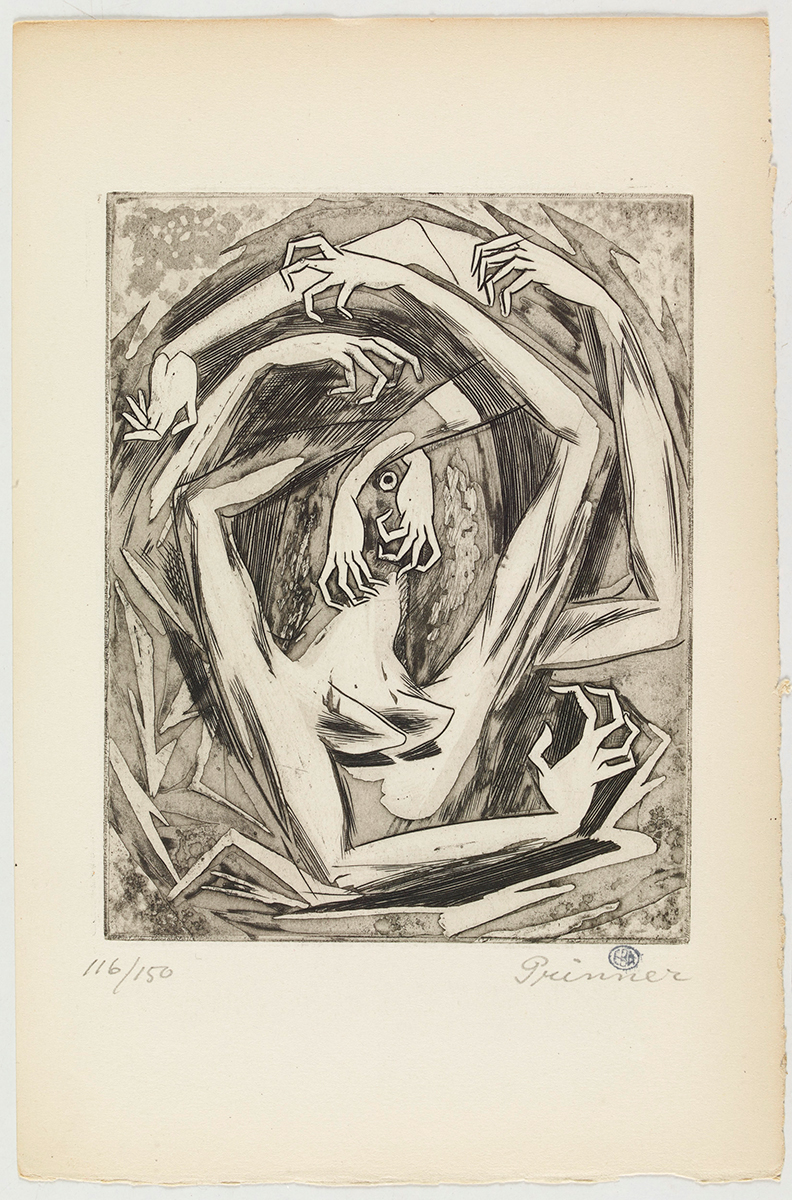

Anton PRINNER (Budapest, 1902 - Paris, 1983)

La Femme tondue, Paris, A.P.R., 1946, artist's book, [58] p., 8 original engravings, 8° 26242

Born in Budapest in 1902, Anton Prinner studied at Beaux-Arts de Paris from 1920 to 1924. He left Hungary at the age of 25 and arrived in Paris in late 1927 or early 1928.

Prinner always refused any influence and especially the confinement in a school. Nevertheless, upon his arrival in Paris, he frequented the Grande Chaumière and the Montparnos milieu, especially the artists from the East but also the South American colony. Prinner's specialists distinguish a constructivist period in his work from 1932 to 1937, which ended with two figurative sculptures, Double Personnage and Femme-taureau. The meeting with Picasso in 1942 had a great influence on the artist, who nevertheless allowed himself to be convinced by the publisher Godet to join the Tapis Vert studio in Vallaris, which marked a period of withdrawal from social life but also of artistic enrichment from 1950 to 1965.

At the same time that he leaves his native country, the artist changes sex. The young woman with pigtails gave way to a man dressed as a worker with a Basque beret to hide his hair. While there is no militant display in this sex change, the fact remains that the question of gender, and more specifically of the androgynous, runs through Prinner's work from the moment it becomes figurative at the turn of the 1930s. As Emmanuel Pernoud notes, "Prinner pushes equalization to the extreme. The figure is regularized in its posture and features, governed by an implacable symmetry that erases any hint of individuation. It is sexualized, generally in the feminine, but the sexual differentiation is content with clues and does not affect - or rarely - the face, which is enclosed in an impenetrable ambiguity. Prinner's sculpture androgynizes form: she raises statues with reunified bodies not by creating hermaphrodites but by equalizing proportions and surfaces. "

The Shorn Woman, published in 1945, participates in the reflection on gender and more particularly on the question of androgyny. The choice to treat the tragic fate reserved for women convinced of having "compromised" with the occupier is not insignificant. Through these shaven women delivered to the popular vindictiveness, it seems that Prinner wants to put in light a certain frustration of humanity when it is put in front of the completeness represented by the Platonic androgyny.

La Femme tondue, Paris, A.P.R., 1946, livre d’artiste, [58] p., 8 gravures originales, 8° 26242